Worstedopolis: The Ascendancy of Bradford in the Global Wool Trade during the Industrial Revolution

Nestled in the heart of West Yorkshire, the city of Bradford might not immediately conjure images of global industrial might. To people unfamiliar with the area, it might just be somewhere near to where the Brontë sisters wrote their novels. Yet, just over a century ago, this vibrant northern hub held an undeniable, powerful charm and status as the undisputed Worstedopolis, the wool capital of the world. The moniker Worstedopolis was coined by Bradford historian William Cudworth in 1888 as it paired together the wool in worsted, and the monopoly the area had on the industry. Harking from humble beginnings as a market town, Bradford underwent a breathtaking transformation, driven by an insatiable demand for its specialised worsted cloth and the relentless march of the Industrial Revolution. This is not just the story of economic boom; it is an epic tale of innovation, enterprise, and the sheer human will that reshaped a landscape and redefined an industry.

The initial growth of Bradford’s textile economy was rooted in the medieval era, but its transformation into a global manufacturing hub was fundamentally a product of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century. This spectacular ascent can be analysed through several interlinking factors of industrial geography and technological innovation. The town benefited from a crucial trifecta of natural resources: readily available coal provided the power necessary for steam-driven machinery, plentiful local sandstone served as the primary building material for the expansive factory system, and its unique access to soft water was essential for the delicate cleaning and dyeing of raw wool. These geographical advantages paired with key technological advancements, such as the mechanised wool-combing machines pioneered by local industrialists like Samuel Cunliffe-Lister, resulted in unparalleled productivity. This convergence established Bradford as the central node in the global wool supply chain, enabling it to process an estimated two-thirds of Britain’s total wool output by the mid-1800s and at its height employed around 70,000 people.

This industrial supremacy led to profound demographic and architectural consequences, manifesting the classic characteristics of a Victorian Boom Town. The town’s population exploded, rapidly expanding from a modest 13,000 residents in 1800 to over 100,000 by 1851. This massive influx drew migrants not only from the surrounding countryside but eventually from across the globe. The immense wealth generated by the worsted trade financed a grand building programme, resulting in the splendid Gothic Revival of public buildings like the Wool Exchange and City Hall, which served as powerful physical symbols of civic pride and international commercial power. However, this growth was not without its social and environmental costs; rapid, unregulated industrialisation resulted in severe pollution, overcrowding, and challenging living conditions for the working-class population who powered the mills. This prompted social reforms and experiments in paternalistic urban planning, most famously seen in the creation of the Saltaire Model Village by mill owner Titus Salt, which will be explored more a little later.

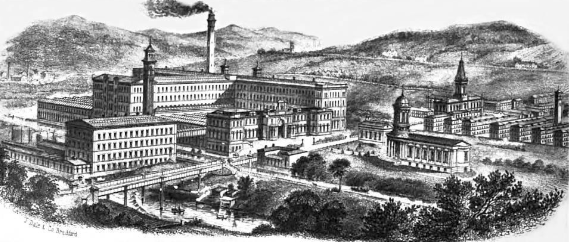

The core of Bradford’s industrial success resided within its colossal worsted mills, which were not merely factories but monumental testaments to Victorian enterprise. These structures, built predominantly from local sandstone, scaled unprecedented sizes and were designed to house the increasingly complex and large-scale machinery required for worsted production, such as Lister’s Mill and Salts Mill. While the exterior architecture often employed grand Italianate or Gothic styles, reflecting the owners’ immense wealth, the interior spaces were defined by the arduous and unrelenting work of the mill hands. Labour was intense and constant; workers, including children, were subjected to long hours, deafening noise, and air thick with wool dust and cotton fluff. Tasks like ‘piecing’, which consisted of joining broken threads, and operating the dangerous combing and spinning machines demanded constant attention, often resulting in injury. These mills, driven by powerful steam engines, ran day and night, forming the harsh, relentless pulse that dictated the economic and social rhythms of Worstedopolis.

Bradford’s focus on worsted was a critical differentiator. Unlike carded wool, which produces a softer, bulkier fabric, worsted wool undergoes a meticulous combing process that aligns the longer fibres, removing shorter ones. This results in a stronger, smoother, and finer yarn, ideal for durable, elegant fabrics used in suits, uniforms, and formal wear. This specialisation allowed Bradford to carve out a lucrative niche in the global textile market, particularly as the rising middle classes across Europe and America sought high-quality, fashionable attire. The demand for worsted seemed insatiable, driving continuous innovation in machinery and production techniques.

Bradford’s strategic location also played a pivotal role in its industrial ascendancy. While not on a major navigable river, Bradford quickly embraced the burgeoning canal network, connecting it to the broader industrial heartlands of Lancashire and the ports of Liverpool and Hull. More significantly, the arrival of the railway system in the mid-19th century revolutionised its connectivity. Raw wool, particularly the prized Merino wool from New Zealand and Australia, could be imported in vast quantities directly to Bradford’s burgeoning warehouses. Conversely, finished worsted cloth could be efficiently despatched to domestic markets and international ports, cementing Bradford’s crucial position in global commerce. This sophisticated logistical infrastructure was as vital as the mills themselves in establishing and maintaining its global dominance.

The entrepreneurial spirit of Bradford’s industrialists was another defining characteristic of its boom years. Figures like Sir Titus Salt and Samuel Cunliffe-Lister, later known as 1st Baron Masham, were more than just factory owners; they were industrial titans who drove technological innovation, expanded global trade networks, and, in some cases, attempted to shape entire communities. Salt, for example, not only built one of the largest mills in the world but also conceived and constructed Saltaire, a model village designed to provide superior living conditions for his workforce, complete with housing, schools, a hospital, and recreational facilities. This paternalistic approach, though perhaps motivated by a mix of genuine concern and a desire for a stable, healthy workforce, stands as a testament to the scale of vision held by Bradford's wool barons. Cunliffe-Lister, meanwhile, amassed a colossal fortune from his innovations in wool-combing machinery, battling fiercely to protect his patents and secure his position as a leading industrialist.

The legacy of Bradford’s "Worstedopolis" era is complex and enduring. While the textile industry experienced a significant decline in the latter half of the 20th century due to global competition, changing fashion trends, and the rise of synthetic fibres, the physical and cultural imprint remains profound. It is important to note that the town’s elevation to its current title was a direct consequence of its industrial might; having swelled to become one of the largest county boroughs in England, Bradford was formally granted city status by Royal Charter in 1897 in commemoration of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. More than a century later, the city continues to harness this deep history to define its future. Many of the grand Victorian mills, once symbols of industrial might, have found new life as residential apartments, cultural centres, and commercial spaces. More than a century later, the city now harnesses this deep heritage, culminating in its current designation as the UK City of Culture for 2025, an honour celebrating its working-class past and diverse, innovative future.

About the Author

Grace E. Turton is an aspiring historical consultant with an MA in Social History and BA in History & Media from Leeds Beckett University. Grace specializes in British and Italian history but loves reading and researching about all aspects of history. In her free time, you can find her exploring the Yorkshire Dales with her dog Bear, watching classic films and playing rugby league. Grace is passionate about keeping history alive and believes that an integral part of this is maintained through History Through Fiction’s purpose.