Don’t Fear the Research: Writing Fiction as an Outsider

For those strange souls who enjoy creating stories and, even stranger, want to share those stories with other humans, there is always a healthy amount of fear. Not self-doubt, but the fear of misrepresenting someone else’s story.

In an age where every critic has a voice, the animosity can be amplified to a deafening roar. Even when writing fiction, errors of authenticity can offend, open old wounds, and also draw accusations of culturally appropriating someone else’s history. For historical fiction writers, finding the seed of a powerful story within the pages of human history can be as thrilling as discovering cash hidden behind your bedroom walls. The narrative, characters, conflicts, all begin to take shape, but then the reality of representing another country, culture, or race’s story becomes a heavy burden and a potential stop sign for progress.

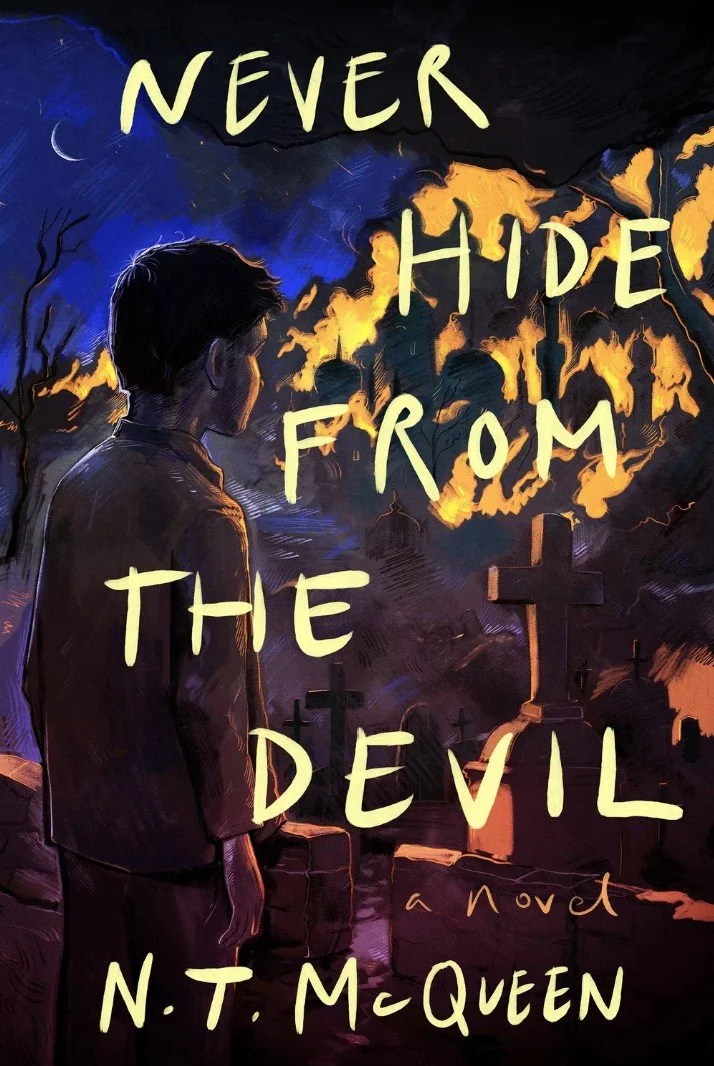

When reading about the Armenian Genocide of 1915, I found one of these gems that would eventually become my young adult historical novel, Never Hide From the Devil. Known as the Defense of Van, it is a tale of resistance where the Armenians of the city of Van fought against the Turkish army and defended their homes against the Turkish army. It was one of those epiphanies where I knew this story needed to be told. But the fear set in: Would the Armenian community want me to write their story?

I knew, in order to make this story come alive, it would require a balance of strategies. Aside from a few character ideas, overarching themes, and a rough plot, I held off writing a first draft until I did enough research to achieve the level of understanding I felt was necessary. After all, I am an odar, a non-Armenian, attempting to tell an important story from their tumultuous history.

From my reading experience, I knew that those outside the culture they were writing about could successfully achieve authenticity and acceptance from the group they were trying to represent. Robert Olen Butler’s A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain, Franz Werfel’s Forty Days at Musah Dagh, and Allen Brenert’s Molokai come to mind as well as countless filmmakers striving for the same goal.

The main question I had to answer was how do I achieve this? What are the appropriate steps? While still nervous about what the response may be, I overcame the fear and jumped into the process and, through my experience, found two techniques that not only helped me overcome my hesitancy, but resulted in an enriching, powerful experience leading to a soon-to-be published novel.

1. Research, Research, Research

It can be easy to fictionalize a historical event or era by labeling it under the excuse of “fiction.” However, fiction is often more scrutinized than non-fiction so taking creative liberties had to be kept to a minimum. In order to do this right, I had to read. Scholarly books, novels based in the same era, peer reviewed articles, websites. This involved countless Google searches which led to links to similar titles which led to more similar titles which led to Youtube videos until I had a massive list of books and articles to wade through. Through this rabbit hole, I came upon a book called Van: 1915 which solely focused on the event which served as the setting for my novel. This became an invaluable resource for me. If there is one positive thing about the internet, it is having countless resources at your fingertips. Where else could you find what type of shoes teenagers wore to school in the Ottoman empire in 1915? But, there was still the nagging question: what will the Armenian community think?

2. Reach Out

I found out books and articles could only tell me so much. It became apparent I needed to reach out to people who knew what they were talking about. Primarily, Armenians. This meant reaching out via email or Instagram to Armenian authors, podcasters, genocide scholars, and others. So, I compiled a list and told them about my project and asked about getting their opinions and insights on the topic. Once I had a draft typed up, I clicked the send button. Now, it was out there. Would I get a response? If so, would they denigrate me for stealing or, worse yet, culturally appropriating, their people’s history? I had to wait and hated every second of it, obsessively checking my emails. Most of the time, I didn’t have to wait long for an answer.

The emails showed up in my inbox faster than I expected. “How exciting!” or “I’m so glad you want to write our stories” were common beginning statements. Even more exciting was the alacrity to schedule a phone call, Zoom meeting, or even send me helpful materials. One connection I made with an Armenian children’s book author led to corresponding with Dr. Khatchig Mouradian, a genocide scholar, who became an endless supply of information that influenced and aided my novel. The host of the podcast Armenian Enough sent me a print copy of her mother’s memoir about her father’s experience surviving the genocide in the Van region. Nadine Takvorian, a graphic novelist, helped me with Western Armenian which Google translate epically failed to do for me. Aram Mjorian, an Armenian author, took time from his busy schedule to discuss Armenian Genocide literature. Though some emails and messages I sent out remained unanswered, the responses I did receive were an overwhelming positive reaction to my novel regardless of my odar status. In fact, most were elated someone that was not Armenian wanted to write their story from an unbiased perspective.

Aside from being excited that their story was being told, almost every Armenian I corresponded with asked the same question: “Why did you want to write about this?” I would assume most cultures and groups want to know the motivation especially if they are from a lesser known population. This is an important question to consider before reaching out to people. Is it because you see yourself on the NYT bestseller list? The possibility of film rights? From my experience, the assumption is they want to know if you truly care about them as a people. They want to know if your motivation is to bring awareness or educate the general population and that you truly care.

Through diligent research and reaching out, my novel came to fruition with more authenticity, acceptance, and reward then I would have imagined. I can’t say with certainty I no longer have jitters about when it will be released into the world next spring and how it will be received. As of now, it is out to blurbers and I’ll catch myself staring off and muttering like Gob Bluth, “I’ve made a huge mistake.” Regardless of my moments, I never would have known the blessing and acceptance I received to write if I had let the fear close the door.

About the Author

N.T. McQueen is a writer and educator based on the Big Island of Hawai'i. He holds an MA in Fiction from CSU-Sacramento and teaches college writing at Hawai'i Community College. McQueen has published two novels and several pieces in various publications. Originally from Sacramento, California, he has participated in humanitarian work in Cambodia, Mexico, and Haiti. He lives with his wife and three daughters and is dedicated to both his family and his craft.

Based on a true story of resistance during the Armenian Genocide…

Fourteen-year-old Suren Simonian lives a typical life in Van, eastern Anatolia, spending his days at school and with his Turkish best friend, Hamza. But in spring 1915, everything changes as rumors of Turkish massacres of Armenian villages reach the city. With Turkish troops massing outside Van, Suren is forced to confront the horrors of genocide. As he struggles to understand what it means to be a man, Suren realizes that when everything you love is threatened, the only answer is to fight back—you can never hide from the devil.