How Humor Finds a Voice in Historical Fiction

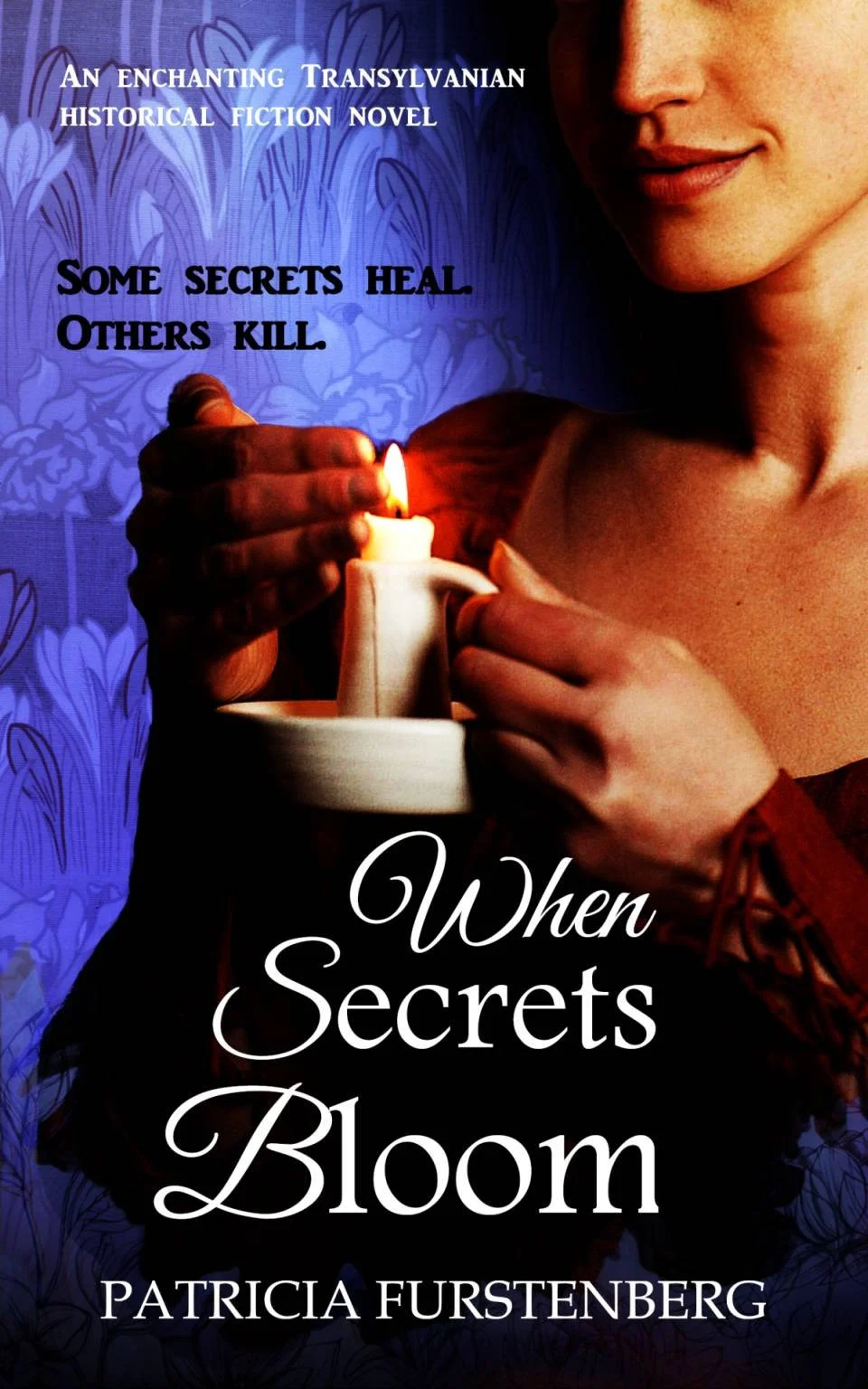

Humor is often seen as incompatible with historical fiction: too modern, too light, or somehow disrespectful to the weight of past suffering. But while writing When Secrets Bloom, I found the opposite to be true. Moments of wit didn’t break the story’s tension; they gave it shape. They revealed character, sharpened emotion and reminded me that survival, especially in dark times, requires more than strategy. It requires spirit.

Far from being anachronistic, humor has always existed, even in history’s bleakest chapters. Whether through gallows jokes, dry observations or absurd superstitions, people have used humor to cope, to resist, and to reclaim a sliver of control. In fiction, these moments offer more than comic relief. They add emotional texture, reflect social tensions and breathe life into a world that might otherwise feel remote.

Humor also opens doors between reader and character. A sly remark, a running joke or that unexpected burst of laughter reveals personality and draws us closer. It deepens tension rather than dissolving it. And, sometimes, the sharpest truths arrive not with a sword, but with a smirk.

As Ralph Fiennes once said, “One of the things that binds us as a family is a shared sense of humor.” In historical fiction, that same wit can bind not just characters, but entire communities. And readers, too. Reminding us that family is also humanity, the need to belong, and the right to be seen and understood, even in the harshest of times.

How Historically Grounded Humor Reflects Cultural Identity and Emotional Resistance

Humor, whether in the form of American sarcasm, British dryness, Yiddish cleverness, Saxon wit, or Romanian superstition, has long reflected cultural identity and offered emotional resistance. Rooted in daily life, it helped people endure hardship and assert a quiet form of agency.

As social commentary, humor allowed ordinary voices to push back against authority. Jokes aimed at politicians, clergy, doctors, or lawyers exposed hypocrisy and reclaimed a measure of control in unjust societies. Across styles and eras, hilarity connects us, softens hardship, questions power and helps us navigate the human condition.

Cultural stereotypes in historical humor often exaggerated traits of the “other”: the lustful French, vengeful Italians, proud Spaniards, barbaric Scots, or the Welsh mocked for their language. These jokes echoed political anxieties and bonded communities through shared definitions of “us” versus “them.”

Gender-based satire, like mocking cuckolded husbands or women “wearing the breeches”, reinforced traditional roles and social order. Such funny language wasn’t always kind, but it revealed cultural tensions and the mechanisms used to uphold them.

What follows are quotes that show humor at work in history: not as mere comic relief, but as a tool of resistance, dignity and shared meaning amid power, loss and absurdity.

“Philip of Macedonia in a message to Sparta... Sparta’s reply: ‘If.’” (Philip of Macedonia): a historical example of dry, laconic wit as national defiance.

“Erasmus says that you should praise a ruler even for qualities he does not have...” (Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies): a humorous perspective on political flattery as cultural survival.

“You need to be more careful, Mo,” she murmured, not unkindly. “This world’s got less mercy than a goose at Michaelmas—and you’re walking around like stuffing.” (Patricia Furstenberg, When Secrets Bloom): the humor lies in the dark, homey metaphor, which both reflects local folklore and emotional resilience.

“The dead are a heap more trouble than the living.” (Flannery O'Connor, The Complete Stories) : some rural humor with emotional resistance reflecting weariness and stoicism.

“I do desire we may be better strangers.” (William Shakespeare, As You Like It, Act 3, Scene 2): Elizabethan insult wrapped in civility, a cultural code of indirect confrontation.

"A map, is it, Vlady?" Frau Rivka said, her voice low. "Let’s hope it shows more than men ever do." (Patricia Furstenberg, When Secrets Bloom): use of irony and wit to veil resistance in front of social norms.

“Sir," she said, "you are no gentleman!" (Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind): it is social rebellion coded in flirtatious banter as well as gender and class tensions revealed in wit.

Humor in historical fiction offers a subtle yet powerful way to expose the norms, hierarchies and contradictions of the past. Far from mere comic relief, it becomes resistance veiled in wit, means to question power, reveal injustice, and deepen narrative truth.

It also bridges past and present. A well-placed jest or inside joke draws readers into the world of the characters, making history feel personal, immediate, and unmistakably human.

How Comedy Helps Modern Readers Connect With Distant Eras and Complicated Truths Through a Simple Inside Joke

Wit in history often emerges as a way to cope with the harshest challenges: war, terror and social tensions become its sharp targets. It connects people, offering shared relief amid hardship. Satire of politics, class and gender bridges the gap between past and present, making history feel immediate and alive. Jokes about universal human flaws reveal that those long ago were as witty and rebellious as we are today.

Through these jests, readers glimpse how people coped with stress, powerlessness, or uncertainty, finding release in laughter. Jokes about universal experiences like bodily functions, infidelity, or class snobbery remind us that those who lived centuries ago were flawed, witty, and quietly rebellious, just as we are today.

Humor also exposes the risks of speaking under authoritarian rule, where jokes had to be shared cautiously, embodying both resistance and resilience. These moments of wit help modern readers relate to historical mindsets, revealing timeless emotions and contradictions.

“Destiny is a good thing to accept when it's going your way...” (Joseph Heller, God Knows): dark irony as a mirror to fate and fairness that resonates across time.

“Maybe all one can do is hope to end up with the right regrets.” (Arthur Miller, The Ride Down Mt. Morgan): a reflective, bittersweet humor on life choices, universally understood.

“There ain't no sin and there ain't no virtue. There's just stuff people do.” (John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath): philosophical bluntness revealing human complexity and moral ambiguity.

“Good men are often more practical than pretty... Andrius just happens to be both.” (Ruta Sepetys, Between Shades of Gray): wry insight into character and values, makes historical suffering feel personal.

“When the end of the world comes, I want to be in Cincinnati...” (Mark Twain): a timeless regional jab that connects with readers through shared recognition of slow change.

“I can handle a cut,” she said at last, her voice soft, laced with a weary smile. “I’ve had toddlers clock me with chamber pots and still ask for pickles.” (Patricia Furstenberg, When Secrets Bloom): cultural wit rooted in everyday struggles and small absurdities

In historical fiction, humor, especially the kind that feels like an inside joke, bridges past and present, acting as social shorthand between characters and readers. It captures the era’s customs and tensions while inviting us into that world. Beyond levity, these moments deepen emotional truth, making humor resilience woven like a secret handshake across centuries. This subtle tool connects us to history, showing how jokes lightens harsh realities and reveals the complexities of human experience, reminding us that laughter was often key to survival amid suffering.

How Humor Can Help Us Deepen Our Understanding Of The Past Because it Improves Serious Situations

Light in the Darkness shows us that humor doesn’t trivialize suffering. It contextualizes it. In historical fiction, laughter becomes a subtle but powerful way to illuminate how people endured hardship, revealing emotional resilience beneath the weight of repression, war, or societal constraint.

Complexity of class is revealed in humor’s evolution, from shared slapstick across all levels to the refined, coded wit favored by the elite in the late 17th century, reflecting broader cultural shifts in manners, shame, and social ambition. This change shows how people expressed identity and status through what and whom they laughed at. While elite wit marked exclusivity, it also retained a subtle subversive edge, gently critiquing the very systems it upheld. Thus, humor acted both as a mirror of social order and a quiet wedge challenging its boundaries.

Empathy through laughter invites modern readers to connect with historical mindsets by revealing the emotions behind what made people laugh. Jokes about tailors or cuckolds aren’t mere comic relief. They expose past fears, desires, and values. Laughter often helped stabilize identity, typically directed at “the other” to reinforce community bonds and manage tension without fully dehumanizing targets.

In historical fiction, this humor shows how people coped with uncertainty, using laughter to affirm their place in a changing world.

“Mr Magyar’s out of town on business,” I managed, my mouth dry as a reed. “Unless this is about a goat, a fever, or a curse, I suggest you try again tomorrow.” (Patricia Furstenberg, When Secrets Bloom): it diffuse tension, illuminate character, and offer ironic commentary, allowing the reader to grasp the gravity of a moment without being overwhelmed.

“The two most common elements in the world are hydrogen and stupidity.” (Arthur Miller): cynical wit as a lens on human error, cutting through the serious with sharp truth.

“The world is a stage, but the play is badly cast.” (Oscar Wilde, Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime): it helps process historical injustice or chaos by framing it as farce.

“To win back my youth... there is nothing I wouldn’t do – except take exercise...” (Oscar Wilde, A Woman of No Importance): ironic take on vanity and aging that softens the melancholy with elegance and deflection.

Thus, humor enriches historical fiction by bringing past social and political tensions to life with wit and satire. It deepens readers’ connection, aids memory and encourages reflection on complex perspectives. More than just comic relief, humor fosters empathy and understanding, revealing the human truths behind historical events and making the past resonate in the present.

Because, sometimes, the sharpest truths in historical fiction arrive not with a sword, but with a smirk.

See more from Patricia Furstenberg in The Role of Storytelling in Literacy:

About the Author

Patricia Furstenberg is a writer of historical fiction inspired by the forgotten corners of the past, where truth and legend entwine. With a medical degree and a heart rooted in her native Transylvania, her stories often explore resilience, hidden truths, and the quiet strength of women. She is best known for her war fiction Silent Heroes and historical fiction Joyful Trouble. Part of an upcoming book series, When Secrets Bloom is her latest release.