Cromwell’s Christmas Crackdown: The Puritan Plot to Cancel Christmas

The festive season. A time of glittering lights, overflowing tables, joyous carols, and perhaps a little too much merriment. For many, it’s a cherished tradition, a break from the everyday, filled with centuries of cultural and religious significance. Yet, for a period in England's history, this very celebration became a battleground, caught in the crossfire of religious zeal and political upheaval. Who was the architect of this audacious attempt to cancel Christmas? None other than the stern, unyielding figure of Oliver Cromwell.

The story of how Christmas came to be banned in England isn't a simple tale of one man's whim. It’s a complex tapestry woven with threads of deep religious conviction, civil war, and a radical redefinition of what it meant to be pious. To understand Cromwell's role, we must first delve into the fertile ground from which Puritanism sprang.

Puritanism: The New Moral Architects

Long before Cromwell’s Protectorate, a movement known as Puritanism had been gathering strength within the Church of England. Disillusioned with what they saw as lingering Catholic influences, excessive ceremony, and moral laxity, Puritans advocated for a "purer" form of worship. They sought to strip away anything not explicitly sanctioned by the Bible, embracing a simpler, more austere approach to faith and life.

For Puritans, Christmas, as it was widely celebrated in the 17th century, was an abomination. They viewed it as a pagan festival, rebranded with a thin veneer of Christianity. The date itself, December 25th, had no biblical basis as Christ’s birth. The revelry – the feasting, drinking, dancing, games, and elaborate decorations – reeked of idolatry and worldliness. They saw it as a day of debauchery, antithetical to the solemn reflection they believed should characterise a true Christian life.

The Christmas traditions of the era were somewhat removed from the cosy, family-focused ideal we might recognise today. It was a boisterous, often rowdy affair, a twelve-day period of carnivalesque indulgence, where social hierarchies were temporarily inverted, and excesses were commonplace. To the Puritans, this was not just unholy, it was a distraction from genuine spiritual devotion.

The English Civil War: A Nation Divided

The simmering tensions between Puritans and the more traditional Anglican establishment, embodied by King Charles I, finally boiled over in the 1640s, erupting into the English Civil War. It was a conflict not just over political power but also over the very soul of the nation's religion. On one side stood the Royalists, staunch defenders of the monarchy and the Church of England's existing structure. On the other were the Parliamentarians, increasingly dominated by Puritan ideals, who sought to curb the King's power and reform the Church.

Oliver Cromwell emerged as a military genius from the Parliamentarian ranks. A devout Puritan himself, he believed unequivocally that God was on their side and that their victory was a divine mandate to cleanse England of sin and establish a truly godly commonwealth. His New Model Army, comprised of highly disciplined and religiously fervent soldiers, proved instrumental in defeating the Royalist forces.

Parliament Takes Aim at Christmas

With Parliament gaining ascendancy, and eventually executing King Charles I in 1649, the opportunity arose to implement radical reforms. The Puritan agenda, long suppressed, could now be enforced. One of their earliest targets was the festive calendar.

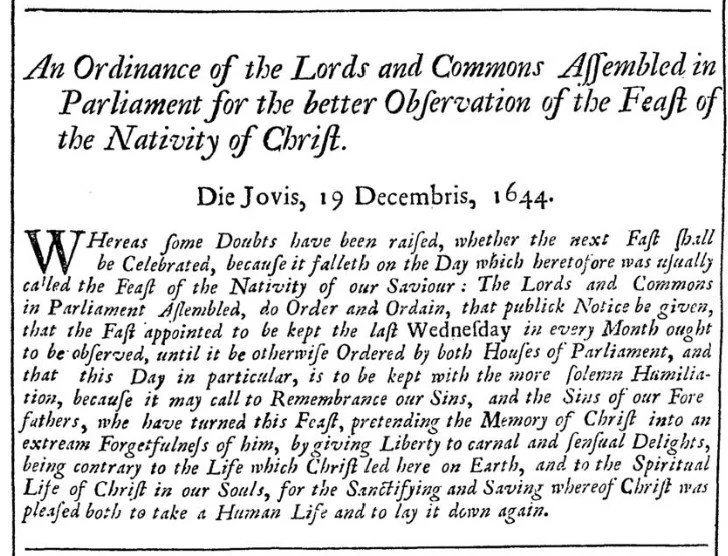

The first major blow to Christmas came in 1644, when an Ordinance of Parliament was issued. It declared that Christmas Day, along with other traditional feast days, was to be observed as a day of fasting and humiliation rather than feasting and celebration. Churches were ordered to remain closed, and shops were to stay open. The message was clear: no more revelry.

This wasn't an outright ‘ban’ in the sense of making it illegal to even mention Christmas, but it was a severe restriction aimed at stamping out public celebration. The rationale was that since the Bible did not specify a date for Christ's birth, and given the perceived pagan origins and unholy practices, it was better to treat it as an ordinary day, or even a day of penitence.

Cromwell and the Enforcement

The execution of Charles I saw England became a Republic, and by 1653, Oliver Cromwell was installed as Lord Protector, effectively ruling the country as a military dictator. Under his leadership, the Puritanical drive intensified. While the 1644 Ordinance had laid the groundwork, Cromwell's Protectorate saw its more rigorous enforcement.

Parliament went further, explicitly banning the celebration of Christmas, Easter, and Whitsun in 1647. Shops were compelled to open, and anyone found engaging in festive activities like feasting, decorating with holly and ivy, or attending special church services faced penalties. Mayors were given powers to fine those who closed their businesses or

indulged in traditional merriment. Soldiers, known as ‘killjoys’ by some, patrolled the streets, confiscating festive food and even arresting those caught celebrating.

The suppression wasn't universally accepted. In many parts of the country, especially in traditionally Royalist areas, people resisted. There were Christmas riots in Canterbury in 1647, also known as the ‘Plum Pudding Riots’. Shops were forced to close, and protestors battled with soldiers, decorating their doors with holly and shouting, "For God, King Charles, and Kent!" Similar disturbances occurred elsewhere, demonstrating the deep-rooted affection people had for their traditions.

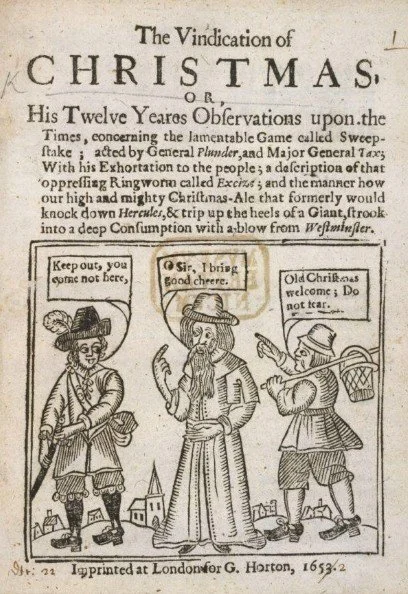

Cromwell, ever the pragmatist and a man who believed in order, understood that stamping out such a deeply ingrained cultural practice was a monumental task. While his government enforced the ban, the private observance of Christmas proved almost impossible to eradicate. Families likely continued their celebrations behind closed doors, albeit in secret and with less outward extravagance. The spirit of defiance lingered, a quiet rebellion against the Puritanical strictures.

Lifting the Yuletide Yoke

Cromwell's rule as Lord Protector ended with his death in 1658. His son, Richard Cromwell, briefly succeeded him but lacked his father's authority and political acumen. The Protectorate quickly crumbled. By 1660, the English people, weary of military rule and strict moral codes, enthusiastically welcomed the return of the monarchy in the form of Charles II, son of the executed King. The Restoration began.

With the Restoration came the joyous return of many things banned or suppressed by the Puritans – theatre, elaborate clothing, and, crucially, Christmas. The Christmas ban was officially lifted, and the festive season quickly reclaimed its place in the English calendar. People celebrated with renewed vigour, perhaps making up for lost time, and the good old days of festive indulgence returned, albeit with a slightly more tempered character in some quarters.

Legacy: A Fleeting Cancellation

Oliver Cromwell's attempt to cancel Christmas stands as a fascinating, if somewhat grim, footnote in history. It highlights the immense power of deeply held religious beliefs to shape public policy and the formidable challenge of altering deeply ingrained cultural traditions. While the ban itself was ultimately short-lived, it left a lasting impact on the collective memory, forever linking the Puritan era with a stern, joyless repression.

Today, the idea of Christmas being ‘cancelled’ feels almost unthinkable. Yet, the story of Cromwell and the Puritans serves as a potent reminder that even the most cherished traditions can become targets in times of profound social and political upheaval. It’s a historical lesson in the enduring human desire for celebration, community, and the simple joy of a festive season, a desire that ultimately proved stronger than even the formidable will of Oliver Cromwell.

About the Author

Grace E. Turton is an aspiring historical consultant with an MA in Social History and BA in History & Media from Leeds Beckett University. Grace specializes in British and Italian history but loves reading and researching about all aspects of history. In her free time, you can find her exploring the Yorkshire Dales with her dog Bear, watching classic films and playing rugby league. Grace is passionate about keeping history alive and believes that an integral part of this is maintained through History Through Fiction’s purpose.