“Let’s Go Exploring!”: An American Cartoonist’s Farewell and a Send-off into New Beginnings, Dec 31, 1995

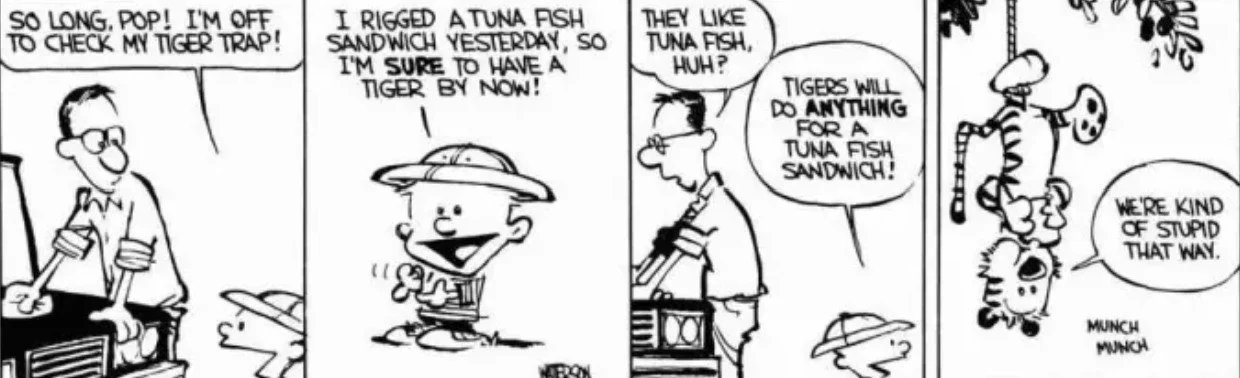

Thirty years ago on December 31st, 1995, Americans across the United States stared at their newspapers in a mixture of emotions; some stunned, others in disbelief, yet more reading in bittersweet acceptance. Cartoonist Bill Watterson had released the final run of his comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, beloved nationwide for its titular characters, the rascally, hyper-imaginative six-year-old Calvin, and his best friend the stuffed tiger, the elegant, wiser Hobbes, his best friend the stuffed tiger. The strip and Watterson had enjoyed a decade of enthusiastic readership and market success. At least, the strip had, ending in its prime. Watterson’s relationship with the syndicates was a tad too complex to call it utter enjoyment.

Still, cultivating an appearance in 2,400 newspapers by ‘95 was quite the mountain peak to walk away from, and it was no stroll up that mountain. Watterson faced a familiar path to all those exploring new frontiers, both artistically and as a businessperson offering his passion, his creation to the market. For a time after being fired from the Cincinnati Post, he had to move back in with his parents and gruellingly work at advertising, while submitting comics to syndicates for four years before Universal Press Syndicate picked up Calvin and Hobbes.

Really not so different from an author drafting their first novel, is it? Not to mention afterwards trying amidst competition and submission criteria to find a suitable publisher Watterson would later have this to say about the process, though.

“The only way to learn how to write and draw is by writing and drawing … to persist in the face of continual rejection requires a deep love of the work itself, and learning that lesson kept me from ever taking Calvin and Hobbes for granted when the strip took off years later.”

But all loves must face outside tests, no exceptions. What was Watterson’s beast of burden?

In an uncomfortable publishing landscape where book distributors and a monopolistic entity like Amazon leverage control through copyright infringement and content violation, creators can feel industrial pressures they never expected to meet. Watterson was no different.

As Calvin and Hobbes collected momentum, companies tried to coax him into licensing his work, turning his characters into merchandise that would sweep lucratively across the American market, even global ones. A modern equivalent might be an author confronted with a publisher who uses artificial intelligence to make book covers, promotional art, or even entertain the prospect of audiobooks through the latest text-to-speech softwares. Whatever sells hot and follows the current trend.

Often a voice against capitalism, exploitation and authoritative institutions through his comic, Watterson resisted this pressure to commercialize his intellectual property, maintaining negotiating leverage only with his relative success. Yet as long as the strip continued selling copies and adorning comic pages of newspapers, the offers persisted.

It wasn’t the only thing Watterson had to deal with from the syndicates. There’s some quiet tension in his final address to readers, where he explains that he has “done what he could within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. He is eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises.”

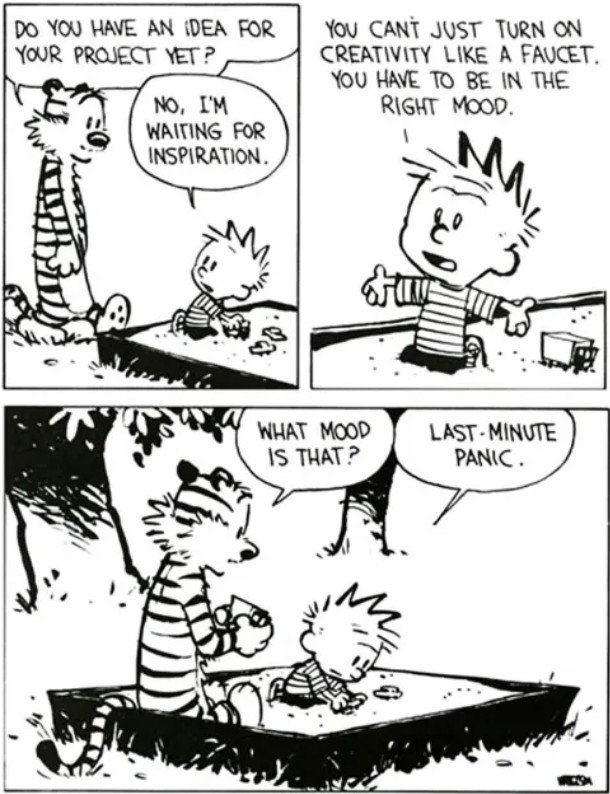

There aren't many storytellers who can work to their satisfaction with a weekly, monthly, even mid-annual deadline (though some of those folks do need to confront their own procrastination, myself included). But a daily deadline? What effect does the crush and pull of twenty-four hours have on the imagination?

Of course, the situation isn’t exactly a smooth translation to the one authors find themselves facing. After all, Watterson crafted his strip out of whimsy, nostalgia, and a reflection of his surrounding world, without the additional toil of research that historical fiction writers need. And producing new stories via four comic panels (which he often fought to expand past) is decidedly not pouring months of work into a novel.

But beneath these technicalities lie common ground. Take authors being prompted by their agents or publishers to complete drafting, let alone editing, their debut manuscript. Or even to write sequels, or turn standalones into series, especially if the original hits a bestseller list. Sequels are all well and good, especially if the material does hold potential for an expansion into new stories, with a receptive audience.

But if neither the author nor the writing journey is ready for such progress, the results could be poor, and often heaviest on the author. And once those suggestions are accepted, not far behind are the deadlines for the new story, similar pressures to the sort that Watterson weathered for a ten-year-stretch.

But let’s look at the message he decided to leave us with at the end of this long road, conveyed through his forever iconic main characters:

Beautiful, simply beautiful. Watterson’s desire to end his long bout with mounting burnout and industrial burdens, and pursue exciting fresh beginnings is still today nothing short of inspirational. He felt that his travels with these two best friends and the readers who had joined him along the way had reached a satisfying and right conclusion. It was time to say goodbye and look forward bravely, even eagerly, to the next new road.

How many of us could say that we’ve done the same since last year? Left behind the comfort zones of old loveless jobs, of rigid schedules that hinder writing, of doubt and fear. How many of us haven’t yet pulled that old draft that we set aside years ago for safekeeping? Reached out to a publisher, even start a bookstore or publishing press? And most importantly, how many of us haven’t put to paper that concept germinating in our heads? I say 2026 is about a good time to start.

Will it be easy? Far from it.

Will it be long? Could be two years. five, twenty down the road. Could be a ten, like Watterson.

But it’s most certainly a new year, a fresh clean start, a day full of possibilities. Let’s go exploring!

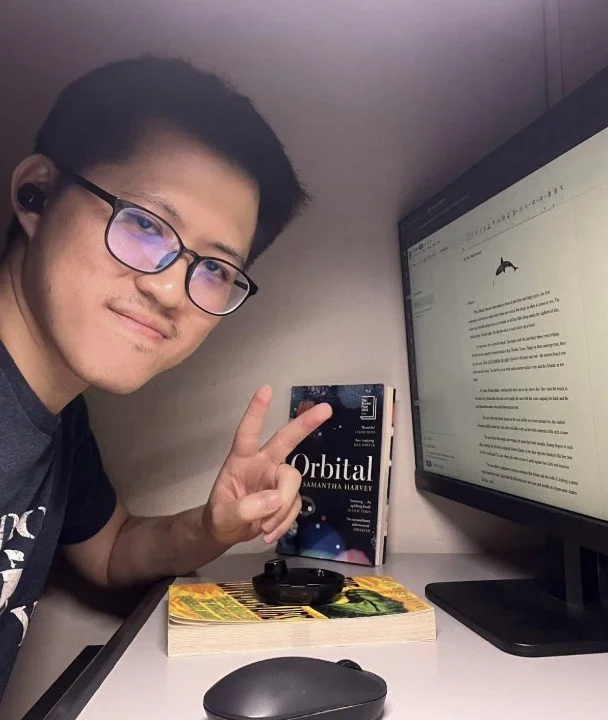

About the Author

Ian Tan is a freelance content editor with a BA in English, Creative Writing from Messiah University, PA. Ian enjoys visiting museums and historical sites, but is partial to researching culinary history, naval history, paleontology, and medieval history. When not spreading his free time amongst his sundry of writing projects, he is often perusing fantasy illustrations on Pinterest or his stacks of yet unread literature. Ian believes the relationship between history and education is crucial, and that when learning is fun, a lot more people can be receptive to consuming more history.