What the Record Couldn’t Hold: Writing The Doctrine of Shadows

A Name at the Threshold

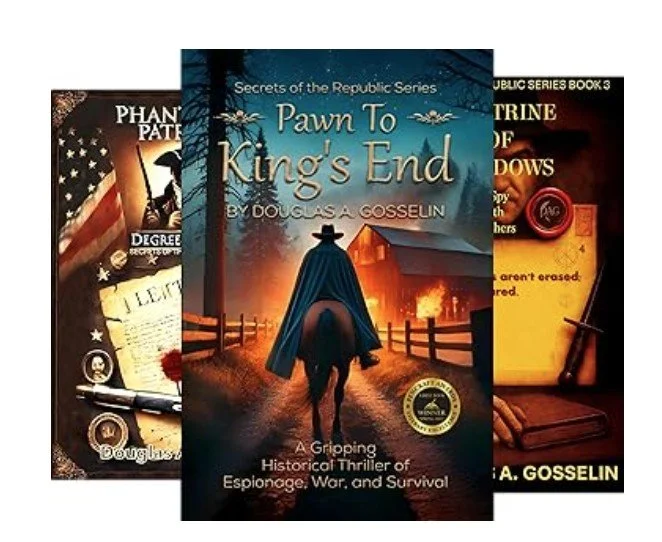

Before The Doctrine of Shadows was written, there was Pawn to King’s End—a novel that asked what would happen if truth, weaponized, were still not enough to save us. That story laid the first stone in a path shaped by surveillance, legacy, and the deep architecture of hidden power.

Then came Phantom Patriot—a work that turned back toward the young Republic itself, peeling back the nation’s self-styled myths and exposing its conscience to the cold light of withheld ideals. It examined what America claimed to be in the 19th century—and what it quietly allowed to survive beneath its promises.

Both novels asked:

Who is protected by freedom?

And more pressingly:

Who is sacrificed to build it?

But it was The Doctrine of Shadows—yet to be published—that demanded the most difficult excavation. The most silence. The most stewardship.

What if the most important labor in America’s founding was not inked onto parchment, not etched into marble, not even remembered?

What if the work that truly preserved the fragile hope of a Republic—the acts that steadied it before it had form—was never signed, never praised, never publicly acknowledged?

What if the names we’re taught were only the loudest, not the most vital?

What if those who shouted liberty were lifted not by their own voices, but by others who whispered it—carried it, concealed it, committed to it not through spectacle, but through sacrifice so quiet it dissolved into the fabric of a history that preferred heroes with titles?

That’s the question that ignited The Doctrine of Shadows—a novel of espionage, of obscured loyalties and uneasy patriotism, of unrecorded service in the shadows of a nation coming into being.

But this story did not begin with plot. It did not arise from the theater of invention.

It began with lineage.

With a search not for fiction—but for fact.

For blood.

For name.

For the spaces where familial memory collided with the archive’s omissions.

I began with Clément Gosselin—a French-Canadian officer in the Continental Army. His name did not echo through textbooks. No monument bore his likeness. Yet there he was—threaded quietly through dispatches and enlistment rolls, barely visible, but present. As I followed his path, it led not merely to a man, but to an architecture of unseen labor—of loyalty without legacy.

He was not alone.

Deeper still, I found Gabriel Gosselin—a relative, yes, but also a cipher of exile. He was displaced during Le Grand Dérangement, the Acadian expulsion that scattered a people before the United States even existed. He was removed not for what he had done, but for what he represented: cultural defiance, religious persistence, the stubborn geography of belonging. Gabriel’s story was not a footnote to the Revolution—it was the prelude. A reminder that erasure often predates history, and that exile is the oldest cost of empire.

Clément and Gabriel were not the center of any conventional tale. They were not the architects of treaties or the commanders of armies. But they were evidence—of how much was demanded of the forgotten before America remembered itself.

And so, The Doctrine of Shadows was written.

Not from mythology.

Not from declaration.

But from silence.

From the names that didn’t survive the syllabus.

From the margins that asked to be read more closely.

From the knowing that not all patriots wore rank—and not all revolutions were loud.

This book does not begin with heroes.

It begins where the archive stops speaking.

It begins in the hush between generations.

It begins with the burden of being unrecorded—

and the resolve to remember anyway.

Finding the Gaps

The research behind The Doctrine of Shadows—a novel yet to be published—was never about dates, battles, or famous declarations. It wasn’t about reenacting what had already been canonized. It wasn’t about polishing old myths or dramatizing names that history had already made permanent. It was about what wasn’t there.

It was a search for absences.

For what the archive chose not to preserve.

For the rooms not sketched in minutes.

For the hands that moved letters but never signed them.

For the eyes that watched but were never named.

I spent years inside the dust of Revolutionary America—not looking for fiction, at first, but for silence. I read congressional ledgers and wartime petitions. I parsed through diplomatic correspondence and burial rosters. I examined inventories from loyalist seizures and notes from backroom committees. But what struck me most wasn’t what was documented—it was what was deliberately left out.

Where were the couriers who rode at night with nothing but secondhand directives and sewn-in ink?

Where were the interpreters who stood between warring tongues, negotiating more than just words?

Where were the wives who shielded letters behind firewood bins and hosted salons designed to overhear more than to entertain?

Where were the widows who became messengers in their husband’s absence—only to be erased again once the war was won?

History records the speeches.

It rarely records the silence.

And yet that silence—that deliberate omission—is where the Republic's survival so often lived.

I kept returning to names like Charles Thomson, perpetual secretary of the Continental Congress. He chronicled nearly every official session over fifteen years, yet his signature appears almost nowhere. His restraint was not absence—it was intention. He witnessed the nation fracture and reassemble from behind the parchment. His voice was the ink, not the echo.

Sarah Livingston Jay, wife of John Jay, moved within diplomatic circles with precision. She orchestrated social leverage in salons and dining rooms, hosting ministers while slipping coded intelligence between conversations. She bore both station and suspicion. The record credits her presence—but rarely her strategy.

Indigenous envoys negotiated peace not as side characters but as sovereign leaders. They sat across from American, British, and French agents, carrying the weight of entire nations on their shoulders. Yet they were dismissed from many official records as obstacles, not actors.

Women, across every colony, passed intelligence hand to hand—from kitchen to garden gate, from church pew to river crossing. Some used embroidery to hide maps. Some used laundry lines to signal when it was safe to move. Most of them remain unnamed.

Loyalists who changed sides—sometimes twice—did not do so for ideology. They did it for their children. For bread. For the unspoken threat. Their stories were filtered through suspicion or erased altogether, labeled traitor when the cause shifted without them.

None of these stories came with statues.

But they were real.

They were vital.

They were the marrow between the bones of what the textbooks recall.

These were not supporting roles.

They were the hidden infrastructure—the quiet scaffolding of a Republic still trembling on its foundations.

And as I read deeper into the ledger of erasures, I understood that fiction would not merely fill the gap. It would have to hold it.

Carefully.

Deliberately.

Like a lantern lowered into a tunnel, not to illuminate every inch, but to prove that someone had once passed through.

And that someone, though unrecorded, still mattered.

Who the Curriculum Forgot

The cast of The Doctrine of Shadows—a novel not yet published—contains both real and composite figures. Each emerged from what the archive preserved, and more tellingly, what it diminished. These were not people wholly forgotten. Many are named. A few even praised. But too often, their roles were downgraded—relegated to the historical equivalent of "also starring."

Not absent.

But backgrounded.

Not unimportant.

Just rarely given the depth or contradiction that defined their actual lives.

They are the ones whose inclusion is brief, whose complexity is bypassed, whose contributions are flattened into single sentences or ceremonial mentions. And in some ways, that partial remembrance—that curated, incomplete echo—is the crueler fate.

James Armistead Lafayette is a name some know. A formerly enslaved man turned double agent, his intelligence helped secure the American victory at Yorktown. He risked his life gathering secrets from British generals, posing as a servant, weaponizing his invisibility.

And yet, after the war, he had to petition for his freedom. The country he served did not immediately recognize him as someone to whom it owed a debt. Even his name—Lafayette—was taken from the man who advocated for his release. He lived out his years as a landowner, and—uncomfortably—as a slaveholder himself.

To be remembered only as a hero is to erase that complication.

To be remembered only as a complication is to ignore the heroism.

His story resists comfort. It demands confrontation.

Esther de Berdt Reed remains a footnote in most narratives, even as her contributions rivaled those of the Founding Fathers in scale and conviction. As the head of the Ladies’ Association of Philadelphia, she mobilized women across the colonies to fund, manufacture, and distribute uniforms to the army—raising over $300,000 in today’s money.

Her writing—The Sentiments of an American Woman—was not an accessory to male patriotism. It was its own movement.

She was not someone who stood behind the Revolution.

She stood beside it—and sometimes in front of it.

And yet, she is usually framed as supportive. Supplementary.

As though contribution from the domestic sphere must always be rendered in smaller font.

Haym Salomon was not forgotten, exactly. His name appears in ledgers and footnotes. But what those records rarely say is that his financial support—given repeatedly, generously, without repayment—kept the Revolutionary army from collapsing.

He was Jewish. He died in poverty. He funded the cause of freedom without ever being welcomed fully into its moral inheritance.

His story lives on in spreadsheets, not in sculpture.

His sacrifice is remembered only in balance sheets, not in songs.

Thomas Paine is more famous than all the rest—but even he, the fiery pamphleteer whose words lit the minds of revolutionaries, was discarded once his ideals grew inconvenient. Common Sense may have stirred the call to arms, but The Rights of Man and The Age of Reason were too radical for a new nation built on selective freedom.

Paine died ostracized. Buried in obscurity.

He did not outlive the revolution. He outlived its tolerance.

He is remembered, yes—but in fragments. In selected quotes.

Not in full.

And then there are those the archive could never fully contain:

Smith, Talia, and Camille are not real in the biographical sense. But they are no less truthful. They were not imagined to add drama. They were constructed to give structure to what history suppressed.

Smith operates like smoke through a keyhole—shaped by ideals, warped by years of training others to stay invisible. He is not cruel. But he is willing to sacrifice clarity for continuity. He carries the weight of a philosophy few ever see.

Talia lives between borders—linguistic, national, and emotional. She is an interpreter of meaning in all its layers. Her fluency is not just verbal, but cultural. She learns what must be said—and more importantly, what must never be.

Camille is not just a woman scorned. She is a record withheld. A cipher in her own right. Her vow is not only revenge—it is memory refined into precision. Her silence is a blade. Her presence a ledger. She does not speak for pain. She speaks for permanence.

These characters embody not what was written, but what was denied the right to be written.

They carry the burden of voices history didn’t delete—but muted.

They are not ornament.

They are not foil.

They are the unwritten proof that not all absence is emptiness.

Some is intention.

Some is resistance.

Some is the price of having once been essential—and then made invisible.

Why It’s Not Nostalgia

I didn’t write this book to glorify the founding era.

And I didn’t write it to complicate it, either.

I wrote it to tell the truth.

The truth, unvarnished—wherever it led.

Without celebration.

Without condemnation.

Without trimming discomfort to make a cleaner silhouette.

The American Revolution was neither divine myth nor total deception. It was a moment of human consequence—full of resolve, hypocrisy, brilliance, and omission. It was fragile. Often improvised. And the nation it produced was stitched together by contradictions, by quiet acts of endurance, and by people who would never be thanked.

Some of those people were erased on purpose.

Others erased themselves, understanding that the work required their absence more than their recognition.

But what united them wasn’t ideology.

It was burden.

It was necessity.

And it was silence.

I did not write this novel to judge them.

Nor to lionize them.

Nor to draw conclusions the record cannot support.

I wrote The Doctrine of Shadows because I believe fiction can hold what history fumbled.

Because story can carry the weight of nuance without asking it to resolve.

Because remembering does not require cheerleading.

It requires attention.

This is not nostalgia.

It is not revisionism.

It is not a weapon or a defense.

It is testimony—gathered with care, told without filter, and offered without adornment.

Not to flatter the past.

And not to shame it.

Only to witness it.

Exactly as it was.

Real People, Truthfully Told

The Doctrine of Shadows rests on a single principle:

The past does not need to be cleansed in order to be honored.

It must be seen clearly—without revision, without flattery, and without denial.

The people in these pages are not flattened into allegory.

They appear in their full contradictions: brave and bitter, wise and complicit, silenced and loud, remembered and forgotten.

Some preserved the nation.

Some preserved only themselves.

But all were part of the Republic’s shadow architecture.

John Jay, humanized, not lionized.

He moved between secrecy and diplomacy, believing that quiet compromise could preserve what public debate might destroy. His silence held the structure, but at a cost.

Sarah Livingston Jay, strategic, not ornamental.

She read salons like others read cipher, navigating power through etiquette, deception, and clarity of purpose. Her intelligence work was neither named nor admitted, yet essential.

Charles Thomson, the recorder of internal fracture.

He documented everything and signed almost nothing. His silence was not absence—it was editorial restraint, shaped by what the Republic could and could not bear to remember.

James Armistead Lafayette, a man whose courage had to be argued into the record.

Spy. Risk-taker. Liberator. Then, later, a slaveholder himself. His legacy does not fit neatly into either celebration or condemnation. It fits only in truth.

Esther de Berdt Reed, whose pen and petition reshaped the role of women in resistance.

She defied both gender and hierarchy with strategy, not spectacle. Her voice turned thread and ink into political force.

Haym Salomon, financier and ghost.

He underwrote the war, then vanished into debt. His name is remembered in footnotes. His faith, too often, not at all.

Tecumseh, leader, strategist, prophet.

He stood not for revolution but for sovereignty. Not for rebellion, but resistance. His vision of liberty challenged the very premise of the new Republic.

Thomas Paine, whose fire lit the Revolution, then burned too brightly for its aftermath.

He was exiled not by enemies, but by the very people his words once carried. The pen that sparked independence was left out in the cold.

Clément Gosselin, the quiet patriot who began my search.

His service was real. His recognition, brief. But his presence was enough to lead me into the margins, where the truest stories often wait.

Gabriel Gosselin, whose exile during Le Grand Dérangement showed me what it means to lose a place before one is ever given.

And then there are the others:

Henry Burrows, whose charm cloaks ambition.

He edits not only words, but people—reshaping truth for those who prefer it neat. A man who sees politics as performance, and performance as leverage. He believes he is saving the Republic. What he is saving is his reflection.

Nathan, whose quiet faith curdles into zeal.

He once believed in grace. He now believes in judgment.

What begins as righteousness becomes something else—obsession, perhaps, or the need to control what cannot be understood.

He is not a villain, but he lets his convictions override his conscience.

John Bellingham, never far from the margins.

His motivations are not wholly clear—even to himself. But his choices leave wreckage, and his silence is not the disciplined kind. It is the dangerous kind.

The unnamed men, who watched suffering and profited.

Who moved between factions, trading loyalty for coin.

Who did not fail to act—they succeeded in evading the burden of memory.

And among them:

Camille, shaped by betrayal, wielding silence as weapon and shield.

Her body is a ledger. Her memory, a blade. Her loyalty is earned, not assumed.

Talia, who straddles languages, borders, and moral lines.

She does not speak unless it matters. But when she does, the world moves.

Cyrus, the orphan archivist.

Raised to observe, trained to remember.

His task is not revenge. It is preservation. He does not flinch when others burn the evidence—he writes it down.

None of these characters were written to comfort.

They were written to reveal.

They do not exist in black and white.

They exist in the unlit space between revolution and reckoning.

Between promise and price.

Their silences are not literary devices.

They are the cost of truth.

And the burden of remembering.

They are not decorations of history.

They are the weight it refused to carry.

They are testimony.

A Chorus of the Unrecorded

This book begins with a simple, haunting question:

Who protected the Republic before it had ink or law to do so?

Before constitutions were ratified or generals remembered,

Who carried the weight of a country that did not yet exist?

The couriers.

The watchers.

The translators.

The women who moved beneath borrowed names.

The servants who overheard too much.

The children placed for strategic reasons.

The orphans given names that weren’t theirs.

The apprentices taught how to vanish.

The midwives who carried more than infants through the night.

The farmers who mapped escape routes beneath their fields.

The seamstresses who stitched dispatches into hems.

The bookbinders who pressed secrets into spines.

The innkeepers who remembered faces but forgot names by request.

The ones who said yes—and then were never seen again.

They were not generals.

They were not delegates.

They signed nothing.

And yet, without them, there would have been nothing to sign.

One figure—a courier—alters his route, not for safety, but to protect a child waiting at a crossroads. His horse limps from an old wound. His coat hem hangs heavy with stitched parchment. He says nothing when he arrives. He leaves only what must be left.

Another—known only by an alias—enters a Federalist tavern along the Hudson. She orders bread. Speaks three lines in French. Slips a coded receipt beneath the tray. The man she betrays will vanish from the record within days. She will vanish before that.

A boy in Boston overhears the word “Saratoga” from the lips of a British officer in the rear of a printer’s shop. He repeats it, quietly, to his sister. She folds it into a weather report and sends it south. The message arrives one week before it would have been too late.

A laundress in New York delivers a bundle of uniforms—one stained with blood. Inside its lining, coordinates. She does not know what they mean. She knows only that her silence is what keeps the map intact.

In Philadelphia, a woman translates a German merchant’s ledger by candlelight. Amid the figures, she finds something else: French names. Destinations. She copies the names. She burns the rest.

These moments are imagined—but only barely.

They are drawn from patterns in the archive’s shadows:

From pension petitions, redacted dispatches, unnamed inventory lists,

From domestic ledgers that read more like riddles than records.

They feel no less true than the declarations preserved beneath glass.

Because this, too, was the architecture of the Republic:

A thousand quiet acts of preservation.

A thousand risks taken in borrowed names.

Even the novel’s structure carries that truth.

A cipher—layered into phrasing, chapter patterns, marginalia—

mirrors the way intelligence once passed in plain sight,

disguised as the ordinary, legible only to those trained to notice absence.

Every silence is deliberate.

Every omission, heavy.

Every break in the narrative is part of the code.

This is the chorus history could not hold.

But fiction—if disciplined, if careful—can still hear it.

And if you’re listening now, then you are part of the structure too.

Why I Wrote It

I write not as a historian, but as someone who has served. Over the course of 25 years in the U.S. Army and Air Force, and more than a decade and a half working across multiple federal agencies, I came to understand a truth that echoes through this novel: that not all service is visible. Not all sacrifice is remembered. And not all records are kept. This book is, in many ways, an extension of that understanding.

Not all truths survive the ledger.

They are misfiled, redacted, forgotten by design—or simply never recorded at all.

But story can carry what bureaucracy abandoned.

It can offer what the archive could not hold:

Voice.

For those who were never asked to speak.

Consequence.

For actions never credited, and choices never praised.

Permanence.

For lives that bore the weight of a country still unborn.

I may never name every patriot who steadied the Republic when it was still trembling.

But I can refuse their second disappearance.

I can shape pages around their silence,

And build chapters where the record left only absence.

Because they didn’t ask for monuments.

They didn’t hold out for parades.

They weren’t waiting for legacy.

But they deserved the ink.

They deserved the truth—not embellished, not cleansed, just told.

So I wrote this for Clément, whose name marked the beginning of my search.

And for Gabriel, whose displacement during Le Grand Dérangement gave exile its shape and memory its urgency.

I wrote this for James, who spied for liberty but had to beg for his own.

For Esther, who armed a revolution with her pen and her ledger.

For Haym, who paid in silence.

For Tecumseh, who showed us that not all revolutions are liberation.

For the courier who vanished before his message arrived.

For the woman whose alias never returned to her real name.

And I wrote it for those whose stories can never be named,

But whose labor held the Republic together between its louder moments.

This novel was never about invention.

It was about remembrance.

And remembrance, when done honestly, is its own quiet act of resistance.

I know that many who read this may carry deeper wells of historical knowledge than I do. I honor that. At the same time, I offer this challenge: find the names that the curriculum overlooked. Search the margins. Pay attention to what was never written down. The Republic was shaped not only by those we remember, but also by those we never saw. Their stories are still waiting to be told. Some of them may belong to you to uncover. And some, perhaps, may one day be told about you.

Secrets of the Republic Series:

Book Three

The Doctrine of Shadows is a historical spy thriller for fans of political intrigue, secret history, and psychological suspense.

In post-Revolutionary War America, freedom survives through secret espionage. Before the CIA, MI6, or Mossad, there was the Doctrine. In 1785, beneath the Pennsylvania State House, John Jay, John Adams, and a mysterious strategist known as Smith launch the republic’s first covert operations program—a bold successor to the Culper Spy Ring that will shape intelligence history.

Unofficial. Untraceable. Unsanctioned.

Ten children are taken from home and trained in ruthless spycraft. They will stand guard where treaties fail.

But one child was never chosen. He was delivered—and his existence could turn the Doctrine’s shadows against itself.

About the Author

Douglas A. Gosselin—former airborne infantryman, law-enforcement officer, and federal contractor turned federal-agency consultant—channels a life spent inside contingency operations conducted in clandestine maneuvers into stories that pull back the curtain on Colonial America and its Revolutionary War espionage. His boots-on-the-ground perspective brings the methods of the Culper Spy Ring and other era-defining spycraft sharply into focus, framing an unflinching look at intelligence history through the timeless lenses of loyalty, strategy, and survival.