Was there a “Rise of the Novel” in Eighteenth-Century China?

One of my favorite works of literary criticism is Ian Watt’s The Rise of the Novel. Watt argues that eighteenth-century England witnessed the creation of the modern novel, by which he means the realistic novel as opposed to the epic, romance, or allegory. The realistic novel attempts to give a full and authentic report of human experience, including the individuality of its characters and the particulars of the times and places of their actions. The creators of the modern novel were, according to Watt, Daniel Defoe, Samuel Richardson, and Henry Fielding.

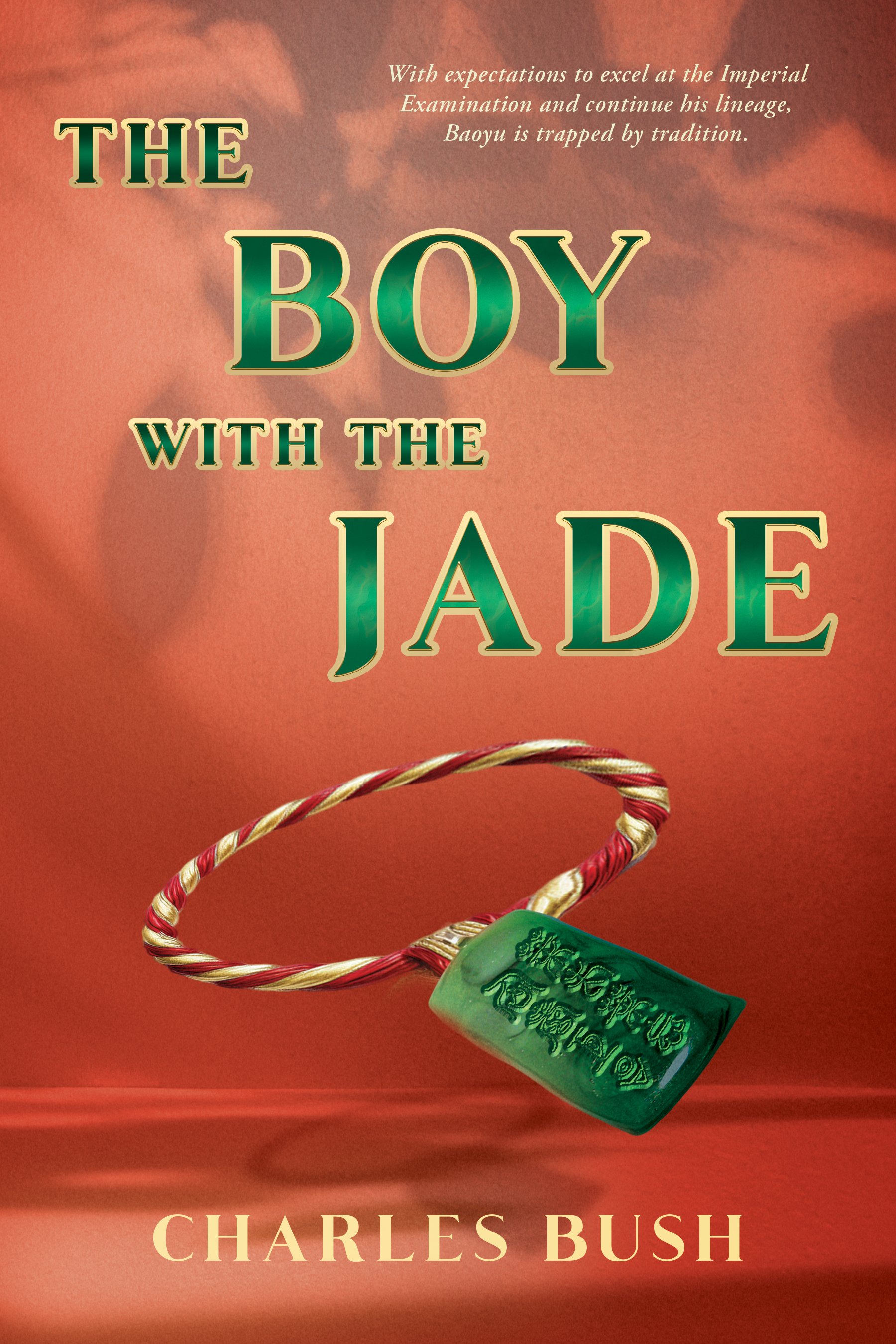

My recent novel from HFT Publishing, The Boy with the Jade, is inspired by an eighteenth-century novel, but one written in China, not England. Entitled, in Chinese, Hong Lou Meng, it has been translated into English under several different titles, including Dream of the Red Chamber, Dream of Red Mansions, and The Story of the Stone.

Using Watt’s definition, Hong Lou Meng can be considered a realistic, and therefore modern, novel. Although it contains elements of allegory and fable, it is above all a work of penetrating psychological realism, a journey into private truth and intimate reality. Even characters of minor consequence are presented as real individuals, not stereotypes.

Was the creation of Hong Lou Meng part of a rise of the novel in eighteenth-century China comparable to the rise of the novel in eighteen-century England?

The answer is no. Hong Lou Meng is an outlier, an isolate. The only other eighteenth-century Chinese novel remotely comparable to Hong Lou Meng is The Scholars. While ranked as one of the six classic Chinese novels, it is not a realistic novel in Watt’s sense. It is more a collection of short stories than a unified narrative, and its characters are types, neither individualized nor probed in psychological depth.

Why was there no rise of the novel in eighteenth-century China?

The advent of the modern novel in eighteenth-century England took place alongside a dramatic expansion of the reading public. Previously, enjoyment of literature had been mostly a privilege of the aristocracy. Now reading spread to the middle class, particularly women.

Along with this came the creation of a publishing infrastructure. At the forefront of this trend were what were then called booksellers. We would call them publishers, for they not only sold books, they also commissioned authors and owned or controlled printers. In eighteenth-century England booksellers increased in both numbers and social standing.

Yet another concurrent development was the rapid spread of circulating libraries. Privately owned, often by booksellers, they charged fees, but the fees were modest, allowing even those of modest means to borrow books.

Compare the situation in England to that faced by the author of Hong Lou Meng, Cao Xueqin. Though details about his life are sketchy, to say the least, it is believed Cao began writing Hong Lou Meng around 1744 and continued writing and rewriting it until he died in 1763. Yet the novel was not published until 1792—almost thirty years after the author’s death!

That is not to say Hong Lou Meng went unread before 1792. The novel circulated in manuscript form, and there is evidence manuscript copies were bought and sold. Creating a handwritten copy of a work more than 800,000 words in length must have been enormously expensive, however, and thus access to the novel would have been limited to a small number of the very rich.

Not only that, most of the manuscript copies contained only the first eighty of the novel’s one hundred twenty chapters. Eighteenth-century China was an authoritarian state ruled by an all-powerful emperor, who from time-to-time launched literary inquisitions. The final forty chapters of Hong Lou Meng depict unjust and unprovoked cruelty inflicted on the Jia family by the novel’s fictional emperor. Cao, his family, and his heirs must have been afraid that if the real emperor under whom they lived got wind of the novel’s damning portrayal of imperial governance, they would be subject to persecution.

Cao Xueqin was a towering genius, someone who created, almost out of thin air, a modern Chinese novel, a work that even today, almost three hundred years later, is still regarded as the finest work of imaginative literature ever created in China.

But he did not create, could not have created, a literary movement. China was not fertile ground for that.

About the Author

Charles Bush, a former attorney turned novelist, hails from Kansas City, Missouri. He holds history degrees from Harvard College and the University of California, Berkeley. However, due to a challenging job market for historians, Charles pursued a law degree at the University of Chicago. After a successful legal career, he began transitioning to writing fiction in the early 2000s.

His legal background inspired his first two novels. What Went Wrong with Oscar Toll? tells the story of a San Francisco attorney striving to save a mentally challenged man from death row. Houseboat Wars explores the unique houseboat communities of 1970s Sausalito, where legal battles and personal dramas unfold

Drawing inspiration from Hong Lou Meng, Bush's novel weaves a rich narrative of love, grief, and self-discovery. The Boy with the Jade explores the intricate human quest for meaning, transcending both time and culture.

A fascinating historical novel with a young protagonist who admirably endures severe hardships. Bayou is a seeker and deep thinker who inspires pity with his moral flagellation while showing us that no one is immune to the caprices of fate.”

– Kirkus Reviews