The Enduring Soul of China: A Journey Through the History of Jade

Among the treasures of Chinese art, a single material consistently captivates: jade. In China, it is not merely a gemstone but a profound cultural touchstone, a symbol deeply ingrained in its history, philosophy, and very identity. Spanning more than 7,000 years, jade’s narrative traces an incredible evolution, from simple implements to emblems of imperial authority, spiritual profoundness, and unmatched artistic brilliance.

The Shuowen Jiezi determined that jade was:

A stone that is beautiful, it has five virtues. There is warmth in its lustre and brilliance; this is its quality of kindness; its soft interior may be viewed from the outside revealing [the goodness] within; this is its quality of rectitude; its tone is tranquil and high and carries far and wide; this is its quality of wisdom; it may be broken but cannot be twisted; this is its quality of bravery; its sharp edges are not intended for violence; this is its quality of purity. (Translation adapted from Zheng Dekun)

Beginnings in the Earth: The Neolithic Dawn (c. 7000 BCE - 2000 BCE)

Our story begins in the misty dawn of Chinese civilisation, during the Neolithic period. Archaeological digs have unearthed many of the earliest jade artifacts, dating back over 7,000 years. Cultures like Xinglongwa and Hemudu used jade for basic adornments like beads and rings, and surprisingly, even for some early tools. Jade’s inherent toughness, combined with its beautiful, understated lustre, immediately set it apart from ordinary stones. However, it was the later Neolithic cultures that truly elevated jade. The Hongshan culture (Northeast China) is famed for its captivating zoomorphic jade carvings, most notably the ‘Pig-Dragon’ (Zhulong) which is a coiled, mystical creature often seen as a precursor to the majestic Chinese Dragon. These pieces, often found in tombs, hint at early shamanistic or totemic beliefs.

Further south, the Liangzhu culture in the Yangtze River Delta area, took jade artistry to even more unprecedented heights. They produced astonishing quantities of exquisitely carved jade, notably the enigmatic ‘cong’ and ‘bi’. The ‘cong’ is a hollow cylinder with a square outer section, believed to symbolise the earth and have strong connections to ancient rituals, possibly relating to heaven-worship or shamanistic practices. The ‘bi’, a flat disc with a central hole, is widely thought to represent the heavens and was used in rituals relating to cosmological beliefs and celestial worship. The ‘cong’ and ‘bi’ are considered to be a ritual pair and are frequently found together in Liangzhu burials. The sheer scale and intricate craftmanship of Liangzhu jade suggest a highly refined society with specialised artisans and a deeply ingrained spiritual reverence for jade. These early pieces laid the foundation for jade’s profound symbolic role in Chinese cosmology.

The Rise of Empires: Jade as Power and Ritual (c. 2000 BCE – 220 CE)

As China moved into the Bronze Age with the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties, bronze technology flourished, but jade’s significance was not forgotten, it became something more. Jade became the material of the elite, used for ceremonial weapons, even though it was often too delicate for battle, it served as a symbol for authority. The stone was also used for ornate plaques and crucial burial objects. Its perceived incorruptibility made it ideal for funerary rites, as it was believed to preserve the body and spirit.

The Zhou Dynasty further cemented jade’s role in society through the ‘Six Ritual Jades’ which has been noted as the most important development in jade’s narrative. They are as follows: ‘bi’, ‘cong’, ‘gui’, ‘zhang’, ‘hu’, and ‘huang’. These pieces were used in state ceremonies and as symbols of rank, meticulously connecting rulers to cosmic order. Jade was no longer just beautiful; it was foundational to governance and social hierarchy.

The tumultuous Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods saw a blossoming of jade artistry. Carving techniques became incredibly refined, in spite of the political fragmentation. Openwork, intricate incising, and highly polished surfaces became hallmarks of the era. Jade adorned the nobility as elaborate and decorative pendants, belt hooks, and ornaments. They often featured dynamic, intertwined dragons and phoenixes, demonstrating the refined aesthetic tastes.

The unified might of the Han Dynasty, that followed, was a true golden age for jade. The belief in the immortal powers of jade had reached its peak which can be seen in the burial rituals. Emperors and high-ranking nobles were interred in full-body suits made of thousands of small jade plaques, meticulously stitched together with gold, silver, or copper wire. These intricate creations were intended to preserve the deceased and grant them eternal life. Beyond burials, jade was used for exquisite vessels, philosophical objects, and personal adornments. Thereby, reflecting a sophisticated culture obsessed with longevity and cosmic harmony.

From Imperial Splendour to Literati Refinement (220 CE – 1912 CE)

Through the subsequent dynasties, jade continued its central role, adapting to evolving artistic styles and philosophical currents. The Tang Dynasty, known for its cosmopolitanism, saw jade objects incorporate foreign influences from the Silk Road. The Song Dynasty ushered in a period of refined aestheticism and scholarly appreciation. There was a conscious return to archaic jade forms, reflecting a deep respect for history and tradition. Jade carvings embraced subtle designs, emphasising the inherent beauty and purity of the stone, appealing to the refined tastes of the literati class.

The final crescendo in China’s jade story belongs to the Ming Dynasty and the Qing Dynasty. These periods witnessed an unprecedented imperial patronage, especially under the Qianlong Emperor. Imperial workshops produced an astonishing array of jade pieces, varying from colossal mountain carvings to delicate scholarly objects, demonstrating unparalleled technical mastery. It was during the Qing that jadeite, a new, often more vibrantly coloured form of jade, began to be imported from Burma, quickly gaining popularity alongside the traditional nephrite. Qing jade carvings are renowned for their intricate detail, superb polish, and imaginative compositions, cementing their place as masterpieces of world art.

Jade Today: An Everlasting Legacy

Even in the modern era, jade remains a powerful symbol in China. It is not just a precious stone; it embodies virtues like purity, integrity, wisdom, and justice. Qualities adorned by Confucius centuries ago. It is a symbol of good fortune, protection, and enduring beauty. From elaborate jewellery to decorative pieces gracing home, jade continues to be cherished, connecting contemporary Chinese culture to its ancient past.

The history of jade in China is a magnificent tapestry woven with threads of belief, power, and art. It tells a story of a civilisation that saw more than just a stone, but a living essence, a spiritual conduit, and a timeless expression of its soul. As long as Chinese culture endures, so too will the captivating legacy of jade.

About the Author

Grace E. Turton is an aspiring historical consultant with an MA in Social History and BA in History & Media from Leeds Beckett University. Grace specializes in British and Italian history but loves reading and researching about all aspects of history. In her free time, you can find her exploring the Yorkshire Dales with her dog Bear, watching classic films and playing rugby league. Grace is passionate about keeping history alive and believes that an integral part of this is maintained through History Through Fiction’s purpose.

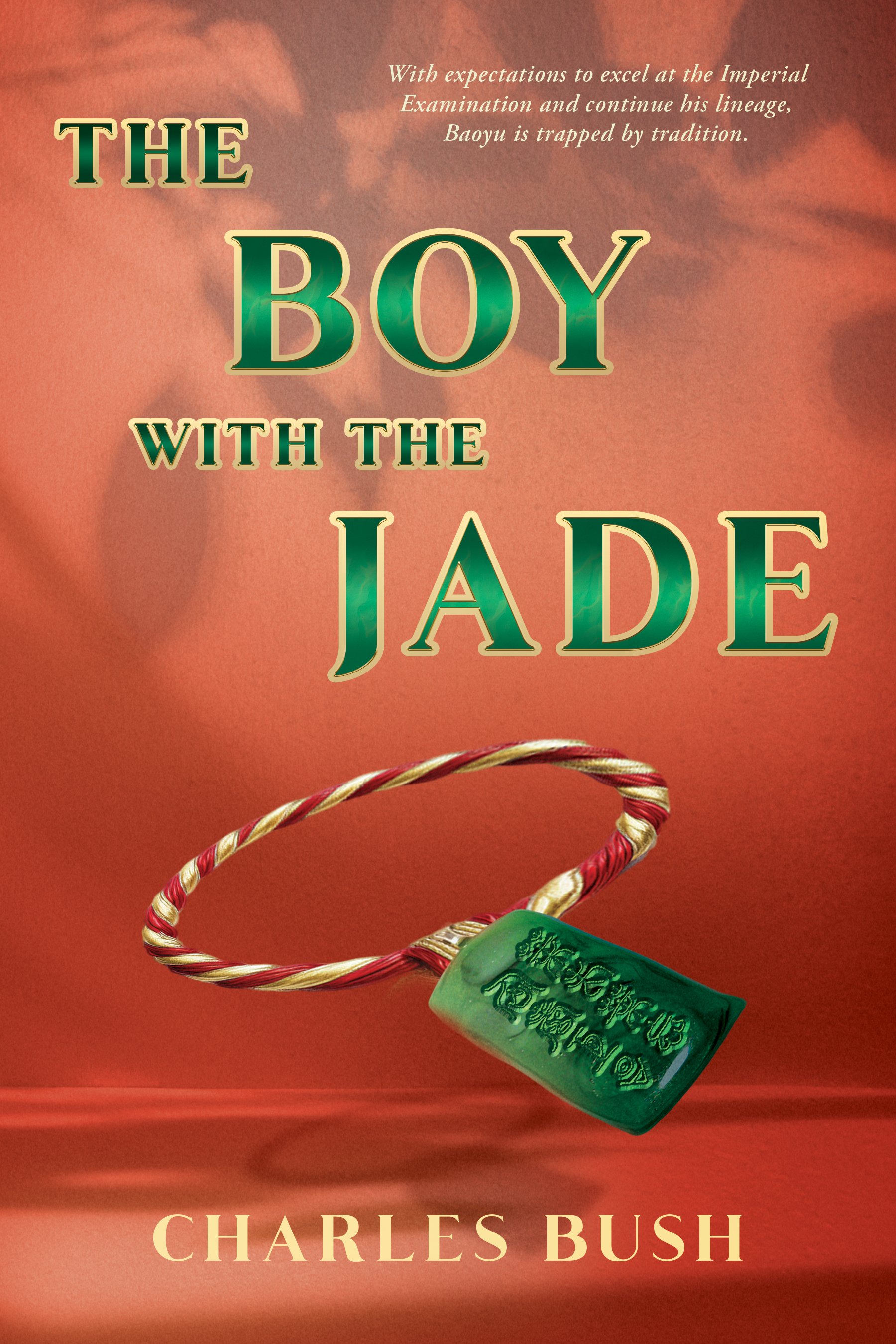

A young aristocrat's quest for identity amid love, loss, and betrayal in 18th-century China.

Baoyu—born with a jade pendant in his mouth and destined for greatness—struggles with love, loss, and suffocating family expectations. After heartbreak and tragedy, he rejects tradition to seek spiritual freedom. The Boy with the Jade is a lush, moving tale of self-discovery, inspired by Hong Lou Meng, that explores the universal search for meaning.

Coming September 16th, 2025