Heroes who did not surrender – Operation Anthropoid in Prague, 1942

Josef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš

Operation Anthropoid remains one of the most extraordinary acts of resistance in World War II. In the dark days of Nazi occupation, two young Czechoslovak paratroopers—Josef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš—risked everything to strike at Reinhard Heydrich, the ruthless architect of the Final Solution. Their mission, launched from Britain and carried out on the streets of Prague, symbolized courage in the face of impossible odds and continues to inspire generations.

29 December 1941 — three elite drops, one priority: payback.

On a freezing night above occupied Bohemia and Moravia, three parachute teams slipped from a Halifax bomber toward the dark fields of their homeland. Their orders were precise. Silver A and Silver B would rebuild the underground’s communications and support. One team carried the top-priority mission—Operation Anthropoid: a direct strike at Reinhard Heydrich, Hitler’s executioner in Prague. The message was simple and brutal—payback for terror.

The man they came for

Reinhard Heydrich—the “Butcher of Prague,” the “Blonde Beast”—ruled the Protectorate as a cold technician of fear. Backed by Hitler, he moved to crush Czechoslovak resistance, cut off its leaders, and break its spirit. He banned the Sokol movement—the civic backbone built on “a sound mind in a sound body”—and sent Sokol leaders to Mauthausen for extermination. In his own words: “Czechs need to know who is the boss here. It is necessary to speak German. Those who will adapt will survive and be Germanized; those who won’t will be sent to concentration camps.” Prague was to be a laboratory of obedience. Anthropoid set out to end the experiment.

A mission meant to echo

The London planners were clear: don’t just remove Heydrich—do it so the world hears it. The assassination had to break the fatalism of occupation, prove that Czechs and Slovaks were still fighting, and force the Allies to face what Munich had cost. These men were not sent to die quietly. They were sent to make history answer.

“A belated Christmas gift”

Weeks of surveillance followed: routes timed, corners measured, rehearsals repeated until muscle memory took over. The local resistance opened doors and risked everything—safe houses, watchers, couriers, forged papers. Among them, a line made the rounds with a lump in the throat: the paratroopers were a “belated Christmas gift that fell from the sky.” The city, beaten but unbroken, began to hope.

27 May 1942 — Heydrich’s Curve

Heydrich’s Curve

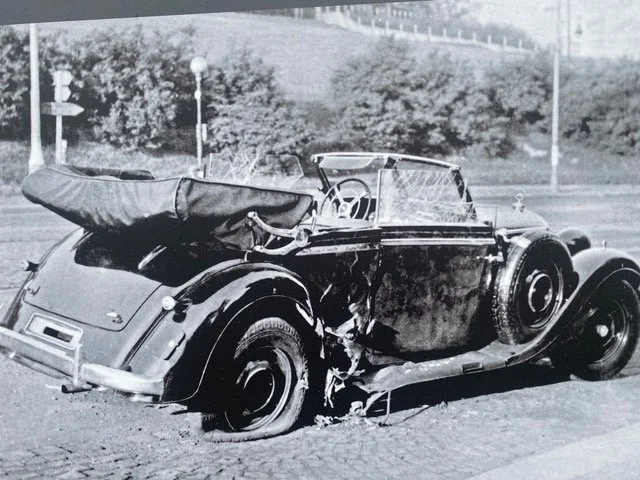

Late morning, the Mercedes 320 Convertible slowed for the tight bend in Libeň that Prague still calls Heydrich’s Curve. Jozef Gabčík stepped into the road and raised his Sten gun. At point-blank range the weapon failed—a cartridge had turned in the fully loaded magazine and the gun did not fire. In the space of a heartbeat, Jan Kubiš hurled his bomb; it detonated by the rear wheel, sending metal fragments and horsehair stuffing through Heydrich’s body.

As shots cracked across the cobbles, Heydrich’s driver Johann Klein made a catastrophic choice: he chased Gabčík on foot, leaving his gravely wounded boss in the car. The assassins disengaged into Prague’s streets. Against all odds, the mission had worked.

Heydrich’s Mercedes 320 Convertible

The city under the boot

Prague slammed shut—raids, curfews, mass arrests—a manhunt on an industrial scale. The paratroopers slipped to the Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius on Resslova Street and hid in the crypt, a stone chamber with a single vent to the street. On 4 June, Heydrich died of infection and trauma. The men in the crypt had struck the head of the machine and lived—so far.

10 June 1942 — Lidice

To terrorise a nation into silence, the occupiers chose Lidice, a peaceful village with no part in the ambush. 173 men were shot in groups by the barns. Most women were deported to Ravensbrück. Children were separated; 82 were murdered in gas vans at Chełmno, a few taken for Germanisation. The houses were burned and bulldozed; the name was meant to disappear. Instead, Lidice became a worldwide rallying cry—proof of what the regime was.

18 June 1942 — the last stand in the crypt

Betrayal opened the final door. Karel Čurda, a fellow parachutist who broke under fear and greed, denounced the network. At dawn on 18 June, about seven hundred Nazi troops sealed off Resslova Street and attacked. Seven men were inside the church.

Upstairs, three—Adolf Opálka, Jan Kubiš, Josef Bublík—held the nave and choir loft against grenades and automatic fire. When the last positions collapsed, two were dying; the third took his own life rather than be paraded as a trophy.

Down in the crypt, four—Jozef Gabčík, Josef Valčík, Jaroslav Švarc, Jan Hrubý—fought by the muzzle flash of pistols as the attackers pumped water through the vents and rolled in tear gas. For over seven hours, the church shook with explosions. When the last magazines were empty and the water rose, the four made their final choice. They did not surrender.

Witnesses remembered the shout thrown back at the loudhailer: “We are Czechs! We will never surrender!” Whether heard that day or kept alive in memory, the line fits the facts. Every action of those hours says the same thing.

Why it mattered

Kobylisy Shooting Range Memorial

This courage cost lives—many lives. But the alternative would have cost a nation’s future. If Heydrich had lived, the machinery of terror in Prague would have tightened still further; the message abroad would have been resignation. Instead, the assassins forced the world to look. Lidice showed, without euphemism, what the Nazis were prepared to do. The British public roared; pressure mounted; Britain annulled the Munich Agreement, and France followed. From that moment, the revival of Czechoslovakia within its original borders after the war moved from hope to commitment.

Operation Anthropoid was designed to echo. It still does—at Heydrich’s Curve, where a car had to slow; at Lidice, where the names are read into the wind; and in the crypt beneath Cyril and Methodius, where the walls still carry the marks. When everything rational said “submit,” seven men chose to stand. And because they did, a nation rose with them.

Art of Your Travel - Martina Gregorcova – Official Guide of Prague

Since 2006, I have run my own travel agency, Art of Your Travel, creating unforgettable experiences for visitors to Prague. Beyond organizing corporate events, bachelor parties, and unique tours in my vintage Trabant 601, my greatest passion lies in guiding Czechoslovak resistance tours. These tours are more than history lessons—they are a living tribute to the men and women who stood against tyranny. I believe it is vital, especially today, to remind people that they too have the right to resist when things are wrong, and that courage in the face of evil matters. For me, it is also deeply personal: to honor the memory of my ancestors, thanks to whom I can exist. As a close friend often tells me, “we must live our lives for them, because they gave theirs for us”—a truth that I carry into every tour I lead.