A Stitch in Time: Avoiding Anachronism in Characters’ Clothing and Jewelry

Is it pedantic to fume at the Titanic movie when Jack tells Rose about his ice fishing on Lake Wissota - a man-made lake formed five years after the Titanic sank in 1912? No it’s not! Attention to historical accuracy is a key part of world building when writing fiction.

This applies as much to the details of characters’ clothing and jewellery as to bigger things like country names (Indiana Jones could not have flown over Thailand). Here are some pointers to getting the little things right.

Legal requirements

In medieval and Tudor times, clothing and accessories weren’t just practical or decorative, but symbolic. Sumptuary laws, particularly from the 13th century onwards, delineated class and strictly controlled who could wear what, down to the colour and fabric.

Richard II’s laws tried to prevent social "blurring" between the rising merchant class and landed gentry. These requirements forbade wives and daughters of tradesmen, yeomen and artisans from wearing silk. They were also barred from wearing veils or girdles embroidered with gold or silver or pearls, all marks of aristocratic fashion.

A 1574 proclamation by Queen Elizabeth I prohibited anyone below the rank of earl from wearing "purple silk" (it was also an expensive colour to produce). A merchant’s wife in scarlet might seem a vivid, visual detail but it would have been both illegal and socially shocking. And if you’re writing a sex scandal, then note that prostitutes in Europe were forbidden from wearing pelts and furs - they were often arrested due to breaching the sumptuary laws.

Ear piercings

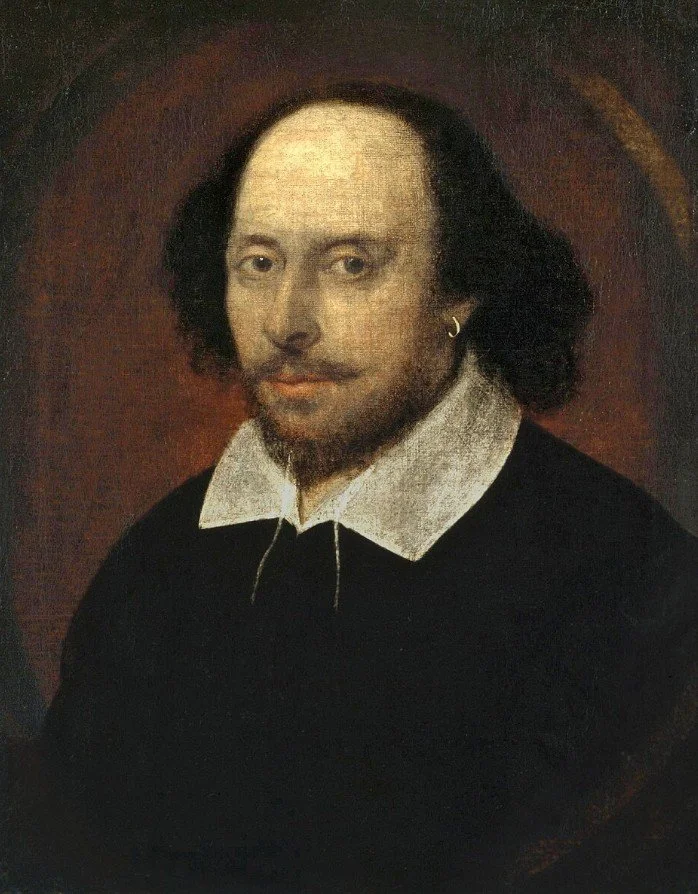

Ear piercing has a complex history in Western fashion. It’s not a cliche for a sailor to have a single gold hoop in one ear in medieval times. And in the 16th and early 17th centuries, ear piercing for men rose in fashionability (portraits of Shakespeare show him wearing one). For women, pierced ears were more common in courtly settings.

By the 18th century, though, earrings were fully fashionable for women but the trend had faded among richer men. And over the next two centuries, pierced ears went through phases of visibility - with styles of hair and bonnets often covering women’s ears.

So if you’re thinking of a character with a piercing, make sure what you’re signalling - it could tell us something about character, status, or foreignness. But exactly what depends on the era.

Shoes

Look down - what have your characters got on their feet? In medieval times, the turnshoe was most common. It was a soft leather shoe sewn inside out and then flipped, often ankle-high with no hard sole. But nobles and courtiers were more influenced by fashion. During the 14th and 15th centuries, the poulaine, a pointed-toe shoe, became notorious, with elite men wearing absurdly long extensions often tied to their shins with chains. Peasants and soldiers had started to adopt sturdier clogs and ankle boots, sometimes with wooden soles. By the late Middle Ages, laces and buckles began to replace simple slipons.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, footwear signalled status. Men wore heeled shoes with red-painted soles at the French court (Louis XIV popularised this, although they are now a trademark of Christian Louboutin) and delicately embroidered women’s shoes were often unsuitable for outdoor wear.

The aglet, the protective tip on a shoelace that makes it easier to thread through eyelets, was popularized by English inventor Harvey Kennedy in 1790. Shoelaces predated him but his invention made them more durable.

The Industrial Revolution brought about more modern trends with left and right shoes finally made distinct in the mid-19th century and mass production making boots and shoes more affordable. Men shifted to flat soles and World War I drove a trend for utilitarian, practical footwear.

Throughout these periods, shoes signaled not just wealth, but gender, occupation and even political allegiance. During the English Civil War (1642–1651), footwear signaled your side. The Royalists, who supported King Charles I, wore flamboyant, high leather riding boots, influenced by French and Spanish court styles. The Parliamentarians had simpler ankle-length shoes or low boots. Unadorned and practical, these reflected their Puritan values.

Cod pieces

Codpieces were real and started as a practical solution to a fashion problem in the 16th century. Men’s tunics were getting shorter, and hose (which were originally two separate legs) left a revealing gap. To preserve their modesty, men used a triangular piece of fabric to cover the opening. In the early and mid-16th century the codpiece was increasingly padded, prominent and decorated, even with jewels. Portraits from this period often featured codpieces. By the end of the century, though, they were mocked and seen as indecent.

Even when popular, they were most common among the nobility and upper classes. Labourers or peasants might wear a more modest codpiece. So think about what your characters are putting on if you describe them getting dressed.

Handling the Victorian era

Queen Victoria reigned a long time, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The Victorian era is often thought of as three separate periods, each heavily influenced by the monarch’s mood. It's a time where the temptation to compress decades into a single “Victorian” look is strong but misleading. A character in 1820 would look utterly different from one in 1890. In particular when the Romantic period (1837-1861) gave way to the Grand period (1861- 1885), following Prince Albert’s death, there was a big shift, Mourning dress and increasingly structured garments, including crinolines and later bustles, reflected both grief and formality. Mourning jewellery was everywhere, especially jet, onyx, and enamelled black pieces, as were bold archaeological revival styles. Come the Aesthetic period (1885-1901), Victorians began to emerge from the long mourning years with flowing, medieval-inspired gowns, new corset styles and elaborate sleeves.

Rings down the ages

Victorian snake rings became popular after Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria a serpent engagement ring in 1839. Image copyright Antique Ring Boutique

Over the last 1,000 years, rings have evolved from symbols of status and allegiance to being much more sentimental accessories. In the early medieval period, rings were heavy, made of gold or bronze, and set with uncut cabochon gems (polished to a dome) such as garnets or sapphires. Gems in jewellery didn’t use the modern cuts that sparkle so much. Diamonds were rare: the prized stones were sapphires, rubies, and emeralds. Symbolism dominated: bishops wore ecclesiastical rings, while aristocrats had signet rings with crests or seals. Craftsmanship centred more on durability and meaning than finesse.

Slowly, who wore what as jewellery changed from a signifier of class in medieval and Tudor times to indicate wealth and capital in the 18th and 19th centuries. In Europe, artisans evolved techniques and adopted styles from other continents. Advances in gem-cutting and metalwork, alongside industrial mass-production techniques, meant rings became more personal objects. The Renaissance saw the rise of faceted gemstones but it was still only relatively recently - the Georgian and especially the Victorian eras - that brilliant-cut diamonds and multi-stone settings became widespread. Even then, symbolism was often rife - such as 19th century acrostic rings which spelled out words like “regard” based on the first letter of the gem names. Around this time, engagement rings began to feature diamonds with increasing frequency.

To sum up

A medieval knight offering a diamond engagement ring to a peasant wearing purple would break the spell of historical authenticity, no matter how compelling the plot. So our advice is DO sweat the small stuff. A wrongly placed ring or shoelace could destroy that immersive experience.

About the Author

Samuel Mee is founder of the Antique Ring Boutique, based in London, and a member of LAPADA and the Society of Jewellry Historians.